- Home

- About

- Books

- Articles

- Insights Insights

- Search Search

- Contact Contact

December 20, 2019. Earlier this year I visited two of the old silver mining cities of Mexico, Zacatecas and Guanajuato. This area is also the homeland of the Huichol people, one of Mexico's 62 recognized indigenous societies.

These reflections on the Huichol struggle to preserve a cultural landscape that is foundational for their identity appeared in Environmental Forum (July/August 2019): The Huichol people number some 45,000 in Western and Central Mexico. They have adapted to modern society but conserve elements of the pantheistic relation to nature shared by nearly all hunter-gatherer groups many thousands of years ago. Huichol culture involves periodic, ritualistic pilgrimages over hundreds of miles visiting sacred natural sites, itineraries which were also pre-Hispanic indigenous trade routes. Various features in this sacred landscape-- caves, springs, mountains, lakes and the ocean itself, as well as animals and plants--are encountered as incarnations of ancestors who through sacrifice helped to create and sustain the world.

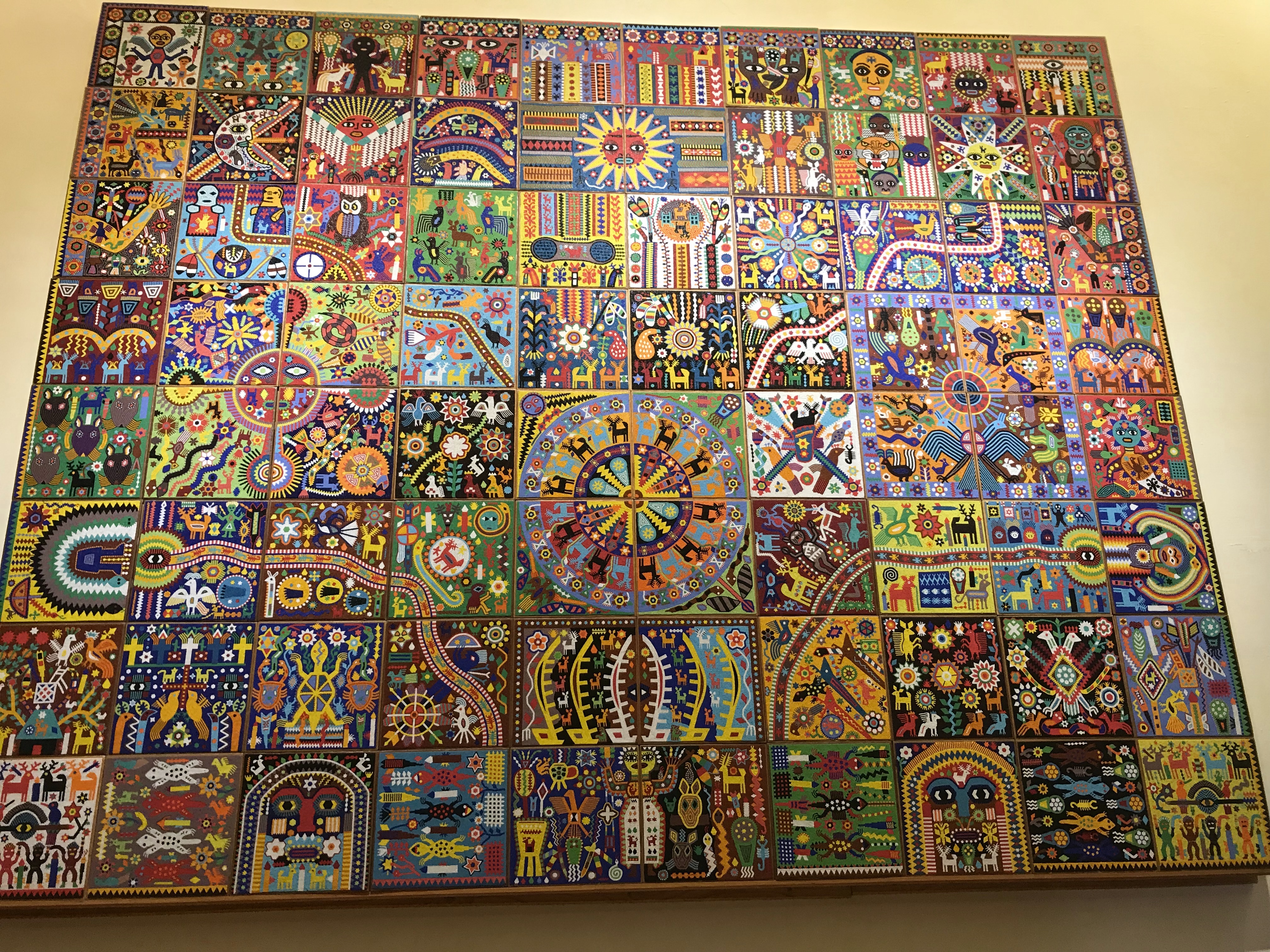

The pilgrimages educate younger chosen Huichol as future leaders who will join the elders. Initiates on the pilgrimage achieve with the help of peyote the visionary power of “Nierika,” the transcendental perception of the structure of the world, inspiring Huichol art. (see examples) below)

The Huichol language remains unwritten; various scholars characterize the sacred pilgrimages as ambulatory “weavings of ritual texts,” “readings of a codex extended on the landscape,” and the Huichol “nomad itinerant university.”

The most important pilgrimage extends 400 miles eastwards from the Pacific Ocean to the top of the Cerro Quemado (“Burnt Hill”) in the sacred area called Wirikuta, a few miles from the old mining town of Real de Catorce in San Luis Potosi state.

Here the Huichol ancestors sacrificed themselves to give birth to the sun, killing the morning stars; they were transformed into those fading stars that the initiates see from the top of the mountain at dawn, disappearing as the sun rises. In Wirikuta the ancestors conducted the first deer hunt, and in the deer’s footprints the first peyote plants grew.

Threats to Wirikuta started with road building in the 1970s that catalyzed logging and agricultural expansion. By the 1990s the Huichol teamed up with a local NGO, Conservacion Humana, together with World Wildlife Fund Mexico and another Mexican environmental NGO, Pronatura, to fight for modifications in highway construction. The coalition succeeded in getting the state of San Luis Potosi to establish Wirikuta as a protected cultural and ecological area in 1994, and its size was doubled in 2000. Wirikuta has been on UNESCO’s Tentative List for confirmation as a World Heritage natural and cultural site since 2004, and WWF has designated the area as one of earth’s three most biodiverse desert ecosystems.

In 2009 a Canadian company, First Majestic Silver, purchased from the Mexican government for $3 million mining concessions covering over 70 percent of the Wirikuta protected area. The concessions are arguably legal since mining will take place in special use sub-zones specifically carved out of the core protection area.

The coalition, the Frente en Defensa de Wirikuta (FDW—Front in Defense of Wirikuta), convinced a Mexican federal court in 2012 to issue an injunction against the mining, citing both Mexican and international law, including International Labor Organization Convention 169 on Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, and the 2008 United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. But attempts to get the Mexican National Commission of Natural Protected Areas (CONANP) to designate Wirikuta as a federal reserve backfired, energizing non-indigenous farmers and community groups in Real de Catorce to file a successful lawsuit against the proposal.

University of Guanajuato research found that many in non-Huichol communities welcome a rejuvenation of mining. The very creation of Real de Catorce and other Spanish settlements in the area dates back to the opening of mines in the18th Century; the region has had a silver mining culture for over 250 years. First Majestic Silver has adopted the discourse of so-called “sustainable mining,” promising $6 million for a local mining museum as well as for the establishment of crafts workshops in silver-smithing and music with stipends for local students. It promises to finance two water treatment plants for Real de Catorce and another community (20 percent of the water will go for the mining, the rest for local use), and has pledged not to use open pit mining nor cyanide. Sustainability rhetoric notwithstanding, the on the ground reality worldwide of many extractive industry investments is one of growing social and environmental abuses—a problematic record in which Canadian mining companies have often been disproportionately involved.

The fate of Wirikuta will reflect whether the overlapping priorities of indigenous rights, biodiversity protection, and economic development, can be reconciled--as species accelerate towards extinction, indigenous cultures around the world die, and, for the Huichol, the places where the sun and the world were born are threatened.